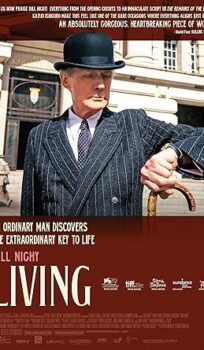

Living(2022)

Submitted by Julio M

Oscar nominee – Best Actor (Bill Nighy); Best Adapted Screenplay.

Short pooper:

Williams (Bill Nighy) dies, but not without finally having been able to leave a worthy legacy behind him: the playground project becomes a reality; people he tried to help attend his funeral; and his City Council protégé Wakeling (Alex Sharp), inspired by a letter Williams left him, visits the playground to reminisce of his mentor’s memory.

Longer version:

His unexpected cancer diagnosis catapults an otherwise lethargic Williams -no doubt, in part, due to the uneventful life he had been leading as a bureaucrat member of the London City Council- to try and make the most of whatever little time he might have left; this, after reconsidering an original thought of ending his life by means of an overdose of sleeping pills. He first befriends an insomniac writer, Sutherland (Tom Burke) -to whom he, instead, gives the pills to help him with his condition-, at the resort town where he’d undertake this deed, and they have a night of drinks and burlesque dancers together.

Upon his return to London, not wanting to go back to work right away, Williams comes across a young former co-worker, Miss Harris (Aimee Lou Wood) and invites her for a fancy lunch upon finding out she had taken a new job at a well-known restaurant -this is seen by a neighbour of Williams’ son Michael (Barney Fishwick) and overbearing daughter-in-law Fiona (Patsy Ferran) and almost leads to a confrontation, but no one acts on it-. After this, he finds ways to spend more time with Miss Harris, inspired by youth and kindness towards him -which she first mistakes as him being infatuated with her, but then acquiesces to, especially when he confides his illness in her-.

As a crowning achievement, Williams decides to tackle the request of the project for converting a derelict building destroyed during World War II into a children’s playground -previously brought to his attention, but thrown under the pile of many other ignored projects, as per the bureaucratic ways of the city and the era-; he coaxes the assistance of his colleagues, including young Wakeling, into convincing the higher ranks of the Council to make the project happen. They are seen taking the walk on a rainy day and, then, the screen goes black.

The next image shows the well-attended funeral of Williams, him having succumbed to the complications of his cancer. Amongst those present, are Michael, Fiona, Wakeling and Miss Harris. At the service posterior to the funeral, a small meeting between Council members happens, showing the project -after an obvious pressure mounted by members of the community- would be a reality. Also, Michael acquaints with Wakeling to personally deliver him a letter Williams had written for the young protégé; and with Miss Harris, only to confirm that Williams hid his diagnosis from him, which makes him feel remorseful.

While riding the commuter train, back from work, Williams’ co-workers comment on how the old man, indeed, showed having had an epiphany towards making the playground project materialize, even if their superiors -particularly a Sir James (Michael Cochrane) who, at first, was a firm opposer to it- managed to take most of the credit for it. A flashback depicts them all visiting the actual bombsite and, later on, Williams’ insistence on having the plans passed and approved through the Council, much to their annoyance and his own satisfaction. They come to believe that he couldn’t have known of his disease, based on Michael’s ignorance of the matter -although Wakely suspects he could have known- and swear to “uphold his example and never elude their own responsibilities respecting this type of change and advancement” -although this doesn’t last; Middleton (Adrian Rawlins) himself, the one who made the oath, is seen leading the apathetic approach from the old days-.

Wakefield eventually reads the letter left by Williams, where the older mentor goads him to remember how, as important as the playground was, it was still just a very small step in the bigger scheme of things and that, whenever he feels the threat of falling into the background -like Williams did, for so long-, to just remember how relevant they all became because of the completion of such small step. Wakefield visits the playground and contemplates it, while a young Constable (Thomas Coombes) approaches him and, in their conversation, the policeman acknowledges having seen Williams before and not having acted upon seeing the old man swinging and singing an old tune under the cold weather, despite how happy he seemed to be. Wakefield reassures him that, indeed, the old man was, at that point, even though he’d die shortly after, the happiest he had ever been in his entire life.

The film ends with visuals of local children enjoying the playground while it still stood.